Reading the Ceiling by Dayo Forster is like a cross between the graphic novel Aya and the movie Sliding Doors. Like Aya, it focuses on  middle class West African teenage girls who frequently make decisions that annoy me. Like Sliding Doors, Reading the Ceiling is structured around alternative histories, examining how things might have been, had one thing gone differently. Or you could see it as a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book with only one decision point! It’s a book that seems to generate mixed opinions, and I can see why, though I ended up liking it much more than I expected.

middle class West African teenage girls who frequently make decisions that annoy me. Like Sliding Doors, Reading the Ceiling is structured around alternative histories, examining how things might have been, had one thing gone differently. Or you could see it as a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book with only one decision point! It’s a book that seems to generate mixed opinions, and I can see why, though I ended up liking it much more than I expected.

The beginning premise is that it is Ayodele’s 18th birthday and she has decided she is going to have sex today for the first time. Never mind that she doesn’t know who that will be. Never mind that she’s not actually excited by any of the possibilities she puts on the list. Despite all that, one way or another she goes through with her plan. After all, what she really wants is just to defy her overbearing mother. Each subsequent section of the book tells the story of Ayodele’s life, depending on which man she ends up having sex with. Have I made it sufficiently clear that I’m not a fan of this premise?

Once I got beyond the initial decision points though, I really enjoyed the rest of the stories. It helps that I’m fascinated by questions of “what would have happened if…” both in my own life and in history more broadly. I recently had reason to consider how the whole trajectory of my career is the result of an e-mail miscommunication with a professor which resulted in my not getting into a particular class in college Instead, I took a different class and the professor suggested we go to a talk by a particular visiting scientist. And so on…

I really think that Dayo Forster handled writing the alternative histories very well. Each history follows Ayodele well into middle age and recognizes that there are many twists and turns in life and there’s no straightforward “good” or “bad” life. While there were differences between Ayodele’s lives, there were also lots of parallels. That makes sense- not every single thing is going to be changed by one decision.

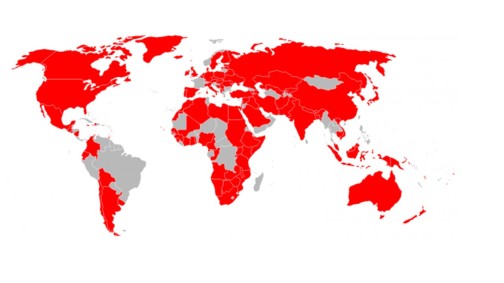

One outcome of being fairly far along in my global reading project is that many aspects of Gambian culture seem familiar from books that I’ve read set in nearby countries. In that sense, I learn a little less from reading a new book now than when I started this project. One the other hand, I have more perspective and can focus a little more on the book itself rather than its unfamiliar setting.

The Gambia is such an interesting country though, tucked in along the Gambia River, surrounded by Senegal. Not surprisingly, water and beaches feature frequently in Reading the Ceiling:

The Gambia was a British colony, while most of the surrounding area was colonized by the French. The Gambia has had encouraging news recently with the president of 22 years agreeing (eventually) to step down when he lost the election. There were only a couple of oblique references to politics in Reading the Ceiling, suggesting that politicians were could get away with certain things and that they had a perhaps surprising ability to buy expensive new cars.

One result of The Gambia being such a small country is that, at the time Ayodele was growing up, there was no university in the country and so anyone who went to college had to leave the country. This meant either having the resources to travel far away to England or the U.S. or else learning French to go to a college in Senegal or other nearby countries. Today The Gambia does have its own university.

Ayodele’s family and most of her friends are Christian (and it is interesting to see how Ayodele’s life experiences shape her religious beliefs), so I got the sense that the country was fairly evenly divided between Christians and Muslims. Actually though, in reading about The Gambia just now, I learned that it is 90% Muslim. That’s a good reminder that reading one book from a country gives one perspective on that country and I should remember that it may not be representative! I do wonder though whether the book might be reflecting differences in religious affiliations between economic classes.

Altogether, I enjoyed the book and would recommend it for people who, like me, are fascinated by alternative narratives, or for people who, unlike me, aren’t bothered when characters make stupid decisions. I’d also be interested to hear recommendations (or disrecommendations) of books with a similar structure.

UPDATED: I’ve just been doing some more reading on the internet and realized that Reading the Ceiling is based on a traditional African storytelling genre, the dilemma tale. Dilemma tales end without a conclusion and instead the storyteller asks a question of the audience. There’s actually an example of a traditional Gambian dilemma tale at the end of Reading the Ceiling, but I didn’t realize that this was an example of a common genre. I’ve now read a few more of these traditional stories and now realize that the intended question at the end of Reading the Ceiling is, “Which of these lives should Ayodele choose?”. (In retrospect, that’s probably obvious and I was just being dim.) I really like that Dayo Forster was adapting a traditional African storytelling technique into the form of a modern novel. It gives me a new appreciation for the book.

but I hadn’t been able to get a copy. I tried ordering it once from my local bookstore specializing in international literature (such an amazing thing to have!) but they hadn’t been able to get a copy. On a second try, it had been published in the U.S. and they were able to get it. I really enjoyed the book and thought it deserved more attention. So I was quite pleasantly surprised when it won the Man Booker International Prize and I started seeing reviews of it everywhere.

but I hadn’t been able to get a copy. I tried ordering it once from my local bookstore specializing in international literature (such an amazing thing to have!) but they hadn’t been able to get a copy. On a second try, it had been published in the U.S. and they were able to get it. I really enjoyed the book and thought it deserved more attention. So I was quite pleasantly surprised when it won the Man Booker International Prize and I started seeing reviews of it everywhere.

However, there’s also an interview with the author at the back of the book in which he states that part of the book is made up of fragments from an earlier, unpublished novel that he wrote with the intention that it could be understood only by himself! So maybe this book is just plain confusing, regardless of where you come from.

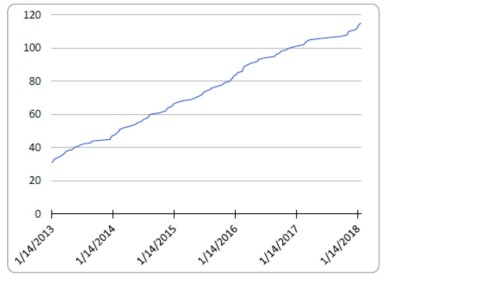

However, there’s also an interview with the author at the back of the book in which he states that part of the book is made up of fragments from an earlier, unpublished novel that he wrote with the intention that it could be understood only by himself! So maybe this book is just plain confusing, regardless of where you come from. I’m kind of impressed at the steadiness of my progress over time!

I’m kind of impressed at the steadiness of my progress over time! The Marsh Arab is a travelogue written in the 1950s by Wilfred Thesiger, a white British man who graduated from Eton and Oxford. It has many of the flaws you might expect from such a book. I wanted to read it anyway because I was intrigued to learn more about the lives about the Marsh Arabs (Thesiger mostly refers to them as the Madan, but that is apparently no longer the preferred term.)

The Marsh Arab is a travelogue written in the 1950s by Wilfred Thesiger, a white British man who graduated from Eton and Oxford. It has many of the flaws you might expect from such a book. I wanted to read it anyway because I was intrigued to learn more about the lives about the Marsh Arabs (Thesiger mostly refers to them as the Madan, but that is apparently no longer the preferred term.)

middle class West African teenage girls who frequently make decisions that annoy me. Like Sliding Doors, Reading the Ceiling is structured around alternative histories, examining how things might have been, had one thing gone differently. Or you could see it as a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book with only one decision point! It’s a book that seems to generate mixed opinions, and I can see why, though I ended up liking it much more than I expected.

middle class West African teenage girls who frequently make decisions that annoy me. Like Sliding Doors, Reading the Ceiling is structured around alternative histories, examining how things might have been, had one thing gone differently. Or you could see it as a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book with only one decision point! It’s a book that seems to generate mixed opinions, and I can see why, though I ended up liking it much more than I expected.

Good popular science writing is such an amazing thing! I’m currently reading I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong which is all about the close relationship between animals and microbes. (If you were wondering, it’s from the

Good popular science writing is such an amazing thing! I’m currently reading I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong which is all about the close relationship between animals and microbes. (If you were wondering, it’s from the